LRU a deeper dive into the classic

The more problems I keep on tackling, the more I find value in this particular problem. Not only because of this problem is constantly brought up during an interview, but also because it is a great example of combination between system design and code implementation.

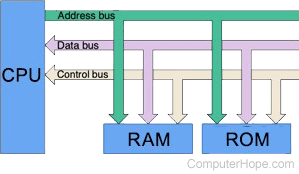

First, let's get the definition right. Usually when we talk about memory, we meant the RAM (ramdom access memory) on your computer.

Though its access speed is not as fast as the CPU's cache memory, it is still lighting fast compare to your computer's storage unit like a disk drive or a SSD which require 'bus' to transfer data - a cool topic that I want to cover in my next post.

But speed comes at a cost. RAM cost much more than a hard drive or a SSD for the same amount of storage, and cache memory is even more so since it is tight up with your CPU. Due to their lighting fast speed, their store sizes are generally much smaller the stardard storage unit. A RAM on your computer is usually between 8G to 32G, and the cache memory on your CPU is even mroe so, averaging about 16KB-128KB for L1 cache per core, 256KB-1MB for L2 cache per core, and 2MB-32MB for L3 cache per core.

All in all, memories, be it cache memory or RAM, are scare resources on your computer that needs to distributed efficiently for the program that requires them. So how can we ensure our memories are being utlizing efficiently? Introducing LRU. There are many design or algorithm that ensure the efficient use of memory, but LRU is probably one of the most famous one of them all. It has been adoped by countless programs across different platforms. A simple, yet powful solution to efficient use of memory.

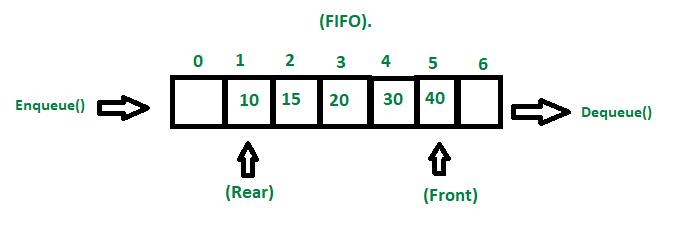

The idea behind LRU is simple, get rid of the item that get to used least amount of time whenever we reach the max capacity of our memory space. Intuitively, this means that we need to some kind of queue structure, where we append each new element into the end (or the start, depending on how you design it), and pop who ever is at the last. That means a simple queue should be enough so solve this problem right? Not quite.

It is guaranteed that we call the element in the queue at some point.

In which case, we need to need to pop the element in the queue and push

it back into to queue to mark its status as a recently used data. If we

are using a native queue structure, this means popping all of the

element before the target element, and re-pushing them back to the

queue, O(n) in the worst case every time we call

get() which is not what we want.

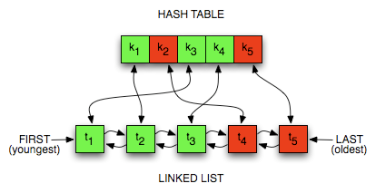

Looking around our tool case, a linked list should be our best shot. The flexibility of a linked list allow us to flexiblely add or remove any element in the "queue". Once an element is called, we will first remove it and then add it after "tail", indicating its status as a recently used data. When we are reaching the max capacity, the node furthest to the "tail" will be removed. Thus creating a least recently used memory.

But only solving add/remove does not help accessing the memory

lighting fast. If we stick to the queue like structure, getting the

value of the insurted key will be O(n) in the worst case.

We could modify the searching with some improvement like start searching

from the "tail" where we are more likely to get a hit of the memory. But

there is a better way to do this. When we think about near

O(1) efficieny access, a hashmap is a great tool to add on

to our existing solution. Even though array provide consistent

O(1) efficiency, its inflexibility caused by fix length

greatly outweight its benefits. Thus a HashMap should be our best shot

here.

Piecing what we have so far. We know we need a linked list for

priority, we need a hashmap for O(1) acccess, and we need a

add/remove helper function to manage the linked list. And thats pretty

much all you need to solve this problem! Let's start with

initlization.

class ListNode{

int key;

int value;

ListNode prev;

ListNode next;

public ListNode (int key, int value){

this.key = key;

this.value = value;

}

}Here is our linked list completed.

class LRU{

int capacity;

Map<Integer,ListNode> dic;

ListNode head;

ListNode tail;

public LRU (int capacity){

this.capacity = capacity;

this.dic = new HashMap<Integer,ListNode>();

this.head = new ListNode(-1,-1);

this.tail = new ListNode(-1,-1);

this.head.next = tail;

this.tail.prev = head;

}

}Here our constructor is completed. Note we linked our dummy head and

dummy tail. Now, let's first complete the needed helper functions.

add() and remove() both manipulate linked

list. For add, we simply add it after tail node. Clean the relation

between previous last node and tail, then adding our current node.

class LRU{

private void add(ListNode nodeToAdd){

ListNode previousLast = tail.prev;

preiousLast.next = nodeToAdd;

nodeToAdd.prev = previousLast;

nodeToAdd.next = tail;

tail.prev = nodeToAdd;

}

}The remove() is more simple compare to

add(). Simply skip it and it is considered deleted.

class LRU{

private void remove(ListNode nodeToRemove){

nodeToRemove.prev.next = nodeToRemove.next;

nodeToRemove.next.prev = nodeToRemove.prev;

}

}Great! Now that we have all the elements, we can start building our

main functions. The core functionality will be completed by

put() and get(). put() is

responsible for updating the frequency priority if the element is

already in of our cache, or create a new element if it is not in our

cache.

public void put(int key, int value) {

if(dic.containsKey(key)){

ListNode oldNode = dic.get(key);

remove(oldNode);

}

ListNode node = new ListNode(key,value);

dic.put(key,node);

add(node);

if(dic.size()>cap){

ListNode toDelete = head.next;

remove(toDelete);

dic.remove(toDelete.key);

}

}get(), on the other hand, is more simple. If our target

is not in the cache, the Map<> should tell us

immediately, in which case, we just return -1. Other wise, beside from

getting the target element back, we also need to update the target

priority.

public int get(int key) {

if(!dic.containsKey(key)){

return -1;

}

ListNode node = dic.get(key);

remove(node);

add(node);

return node.val;

}And there it is! A complete solution is below for reference. LRU is such a classic problem that I found myself often revisiting from time to time. Unlike other problems, which are independent, LRU is more of a complete testing for your programming knowledge. I hope this blog did helped you somehow! Until the next blog, take care.

class ListNode{

int key;

int val;

ListNode next;

ListNode prev;

public ListNode(int key, int val){

this.key = key;

this.val = val;

}

}

class LRUCache {

int cap;

Map<Integer,ListNode> dic;

ListNode head;

ListNode tail;

public LRUCache(int capacity) {

this.cap = capacity;

dic = new HashMap<>();

head = new ListNode(-1,-1);

tail = new ListNode(-1,-1);

head.next = tail;

tail.prev = head;

}

public int get(int key) {

if(!dic.containsKey(key)){

return -1;

}

ListNode node = dic.get(key);

remove(node);

add(node);

return node.val;

}

public void put(int key, int value) {

if(dic.containsKey(key)){

ListNode oldNode = dic.get(key);

remove(oldNode);

}

ListNode node = new ListNode(key,value);

dic.put(key,node);

add(node);

if(dic.size()>cap){

ListNode toDelete = head.next;

remove(toDelete);

dic.remove(toDelete.key);

}

}

public void add(ListNode node){

ListNode preEnd = tail.prev;

preEnd.next = node;

node.prev = preEnd;

node.next = tail;

tail.prev = node;

}

public void remove(ListNode node){

node.prev.next = node.next;

node.next.prev = node.prev;

}

}